László Náray, István Zsadányi

(Published on 23/03/2015 Daily Economy)

“The road-dependent market is where time really matters. Neoclassical economics imagines economics as a road-independent market”. (Lee Smolin)

In our series of articles, we pointed out that the Maastricht criteria system (Mc) was an intellectually defective product of economics. Why? The reason being even at the time of its creation in 1992, there was no economic ground to assume that the financial stability of a hypothetical and continuously expanding EU can only be secured by 60 % government debt rate. Why exactly 60%? Beyond the fact that this number (60%) was the average government debt rate of the 9 Founder States 23 years ago (1991/92), there is no other well-founded reasoning.

In a depressing environment that considers budget equilibrium as a good thing what we must have, extreme political ideas are spreading again, just like in Germany after the First World War. (In the 1920s, the Germans were overwhelmed by a huge obligation of reparation by the narrow-minded politicians of the age.)

Maastricht targets are unnecessarily tight.

In our series of articles, we pointed out that the Maastricht criteria system (Mc) was an intellectually defective product of economics. Why? The reason being even at the time of its creation in 1992, there was no economic ground to assume that the financial stability of a hypothetical and continuously expanding EU can only be secured by 60 % government debt rate. Why exactly 60%? Beyond the fact that this number (60%) was the average government debt rate of the 9 Founder States 23 years ago (1991/92), there is no other well-founded reasoning.

Why 3%? The original mathematical calculation was this:

supposing a 5% GDP growth/year, this 60% government debt rate could be kept with a 3% deficit, so every Member State should keep this 3 percents deficit, regardless of the differences in the initial levels concerning the debt- and deficit rates of the different countries, regardless of the differences in the level of development, wage and price levels, and irrespective to the possibilities that after entering into the EU the free movement of goods and capital will cause serious changes in the capital and income structures in the new and even in the old Member States.

The EU institutional system is based on this static, non-adaptive criterion system. This is merely an unconscious tradition of managing problem, which can only have a pedagogical meaning: it can be used to mock politicians prone to fiscal alcoholism - if the soft budget were the source of the problem. But not now! There seems to be a capital and income distribution crisis!

As a teaching tool, the Maastricht criteria system was built on the belief in the age-old spirit of 1992: they artificially created the possibility of state bankruptcies because they believed that the "market is always right", so spontaneous market processes aiming at cost efficiency can optimally coordinate the placement of the funds for generating sustainable growth.

Insisting on Maastricht Criteria is bigoted ritualism in a hidden way. It is an implicit approval (or a non-awareness tolerance)of an economic vision in which “ the market is always right” and the “deficit and debt is always wrong”. This practice has led to the already weakening internal cohesion of the EU. Europe can once again become the scene of conflicts that threaten the world.

History matters! In the 1970s, stagflation was caused by the fact that oil prices rose more than 30 times in a few years. It was originally inflation driven by oil-resource shock, but after a little time the question was raised: is the inflation still driven by oil price blows or is it already driven by economic actors who are calculating with expanding quantity of money? It seemed timely to test the economy with money-limiting methods. Maastricht criteria fully served the neoliberal response expressed in the 1989 consensus in Washington: only the free market with governments limited by budget constraints would ensure sustainable development, so "de-regulate, liberalize, privatize"!

In the EU barriers between countries have been dismantled, governments have been almost completely excluded from the simulative and protectionist instruments, the common budget of the EU has been set at just over 1 %, national budgets have been limited with a 60% public debt/GDP and a 3 % deficit/GDP ratio, the ECB and national central banks have been banned from financing the budgets, they have set uniform, low inflation targets everywhere - regardless of the differences in starting price and wage levels and its logical implications.

Countries which successfully operated currency unions (prior to the Eurozone creation) had very different budgetary positions e.g the Benelux States, where Belgium had ca. 120%, Luxemburg had ca. 7% public debt to GDP in 1997, or the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

These member states worked without explicit budgetary constraints. The theory of optimal currency areas does not require the quarantine of national budgets, moreover, professionals are directly against this (e.g. Milton Friedman, 1997) because the problem of local (asymmetric) shocks can be managed by a strong central resource allocation or a flexible national budget.

Differences in the level of development of Member States' economies would have required intensive and discretional resource allocation. On the basis of federal convergence experiences, to reduce the developmental differences (ca. 40%) that were much smaller in the examined countries (than they are today between the EU member states), and to treat asymmetric shocks in 1977, the MacDougall Committee suggested to the EU (with 9 member states that time), which EU was not so completely neoliberal at that time, that the redistribution should reach as much as 5% to 7 % of total GDP at EU level.

The neo-classical kind of dogmas based Maastricht Criteria indicated that the EU Creators dropped MacDougall recommendations into the trash, they did not take into account the potential anomalies of the market's self-movement.

Modeling - and factual evidence - shows that the concentration of incomes is growing in the markets which were left to its own resources and without substantial government intervention in money creation. More and more income and wealth go to a thinner and richer layer of society. (British Oxfam reports that 48 % of the world's assets belongs to the richest 1 %.) This is a kind of gravitational force of the monetary universe.

If there is increasingly capital-intensive development, there is a need for fewer employees. The less the employees there are, the lower the incomes of households. Producers, who are pushing their competitors out of the market and have less and fewer employees, will lose their motivation to invest into new production capacities because it became harder to sell their products: the incomes of the “working" or "consuming" class grow slower than the supply of expandable production capacities. Money and capital markets can bridge this dynamic discrepancy: winners' money was channeled to creditworthy but “relatively risky debtors” as consuming or development credit, thus increasing their consumption capacity and, therefore, their indebtedness. Money is created (multiplicated) by lending and can be erased by paying back, so this process is the growing effect of the banking system on influencing the quantity of money. If there is more debt then there are more savings too.

What does "creditworthy" but "relatively risky debtor” mean? We first illustrate the way as to how an emerging region becomes more and more credible, and then we show why credibility growth may hurt them later and how the Maastricht Criteria system contributed to this.

The EU countries were characterized by significant differences in development, and the price and wage levels of underdeveloped countries were significantly lower than those of the developed countries. For-profit maximization reasons, outsourcing of production capacities to underdeveloped regions with lower wages has started. Due to the relocation of production, in underdeveloped regions previously unavailable wage volume appeared, and the rise in wage levels had a price-raising effect.

On the other hand, outsourcing has limited wage increases in developed countries and curbed price increases while boosting capitalists' profits. The relative winners were investors from developed countries. Their profit grew rapidly, their banks could raise funds at low-cost rates, while they realized the relative larger rate of growth and wage increases in underdeveloped regions. This means improved creditworthiness and credit demand. At the same time, due to higher inflation, the interest rates were higher than in developed regions, which offered a significant additional profit to the financial system. The asset prices - as collateral values – increased in the underdeveloped regions, while a growing amount of deposits - as credit oversupply - pushed down the euro interest rates. Due to the different interest rate between developed and underdeveloped countries, and due to the price convergence of the underdeveloped countries, the real interest rate became very low or negative and further increased indebtedness.

Where central banks tried to curb this process with high-interest rates, the market interest broke out through financial innovations, e.g. "lending in foreign-denominated currency".

The majority of the “relatively risky debtors” became net indebted, and the developed countries - mostly due to the fact that more wealthy people live there - became the net creditor.

We can see that the free market is prone, over time, to gradually build up a supersensitive private credit and debt structure, albeit making rational decisions before every step, which becomes increasingly dependent from growth prospects and market sentiment.

The Maastricht criteria system, as the EU's macro-economic framework, supported further the market-generated indebtedness process.

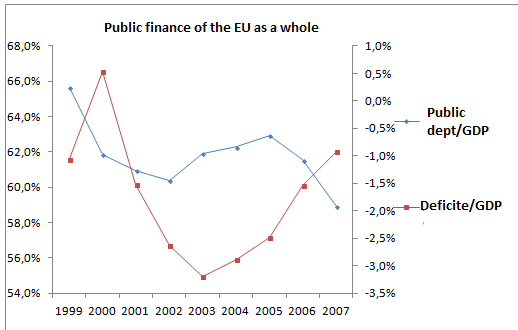

It seemed to be rational to look for credit in underdeveloped countries because of the increasing wage level and GDP growth. Macro risks of lending seemed small, respecting the fact that the indexes of the countries improved according to the sense of the Maastricht criteria system. There is a widespread self-destructive theory, which states that the EU got into trouble because its leaders and investors were too lenient with the violators of the Maastricht criteria. Although overruns have occurred, by 2007, in most EU Member States, the budget deficit per GDP ratio was within the 3% criterion, so this could not have caused a crisis.

On the other hand, the relative and absolute losers of the income distribution - according to EU rules - could not be bailed out using the tools of protectionism or by a central bank which might finance the deficits. The huge part of the private sector mostly in the underdeveloped countries - whose ability to pay mostly depended on the dynamics of income generation - could only integrate into the process if they applied for credit.

The EU got into trouble precisely because its system worked efficiently according to the original intention of its creators.

Instead of the states, the money market took charge of supporting the catching-up process, the banks actively and creatively used and multiplied the amount of money. In the framework governing the EU economy, a large, growth-sensitive, interconnected credit and debt structure have emerged, but following the US financial crisis, only the responsibilities of the debtors were named as the scapegoat for the European liquidity panic. Instead of releasing the income flow problems of the private sector by increasing government spending, the decision-makers had to make austerity actions to avoid the insolvency of the state.

External debt data became suddenly market influencer news, thoughtless fear from “debt” led to real liquidity turmoil. The income and GDP growth slowed down. This had a serious impact on those poorly capitalized, indebted companies, especially in the underdeveloped countries, whose solvency was heavily reliant on the growth rate of the economy. The stagnation of GDP growth has triggered insolvency chains. As lending has created money, forced paybacks could have resulted in money destruction. Liquidation also meant confiscation of money and collaterals available in the sensitive regions, and this has led to economic depression.

Due to the Maastricht system, national budgets were forbidden to intervene in the depressed markets by increasing their demand. The budgets have passively suffered the consequences of the fall in markets (supply and demand), i.e. their incomes fell along with their economies. The expenditure side could not adapt to it. Expanding deficits and government actions to avoid the collapse of the banking system have greatly increased public debt to GDP ratio. As central banks were banned from budget financing, there was a risk of sovereign default, which became a tangible reality for Greece.

The Maastricht criteria system was founded on debt and deficit per GDP ratio meanwhile the central bank rules artificially created the possibility of state bankruptcy.

Obeying these rules, the governments reacted with money-tightening measures, so the effects of spontaneous market panic waves were brutally aggravated.

Due to the lack of EU-level resources for dealing with asymmetric shocks, and the total lack of related procedures, governments have mostly focused on their own indicators by 2011, with almost no means to address the economic disruption of private debt chains. In these circumstances, the improvement of deficit ratios and the imposition of "structural reforms" to meet the criteria only spurred the negative demand-supply spiral. The effect of "reforms" aimed at improving public debt and deficit ratios is disappointing: the euro area average government debt ratio has risen by about 30 percent. The framework has unnecessarily deepened and extended the crisis.

In the quest for the way out, the decision-makers were most afraid that the system would break down and nothing remains in control. The neoliberal interpretation of economic developments was accepted by those too, who do not consider themselves neoliberal, but are afraid of 'taxpayers' money'. The narrow-minded neoliberal rhetoric of taxpayers' interests (that is, unconscious dread of government debt that could be financed at any time by the central banks) resulted in the solution being brutal: they decided to tighten the Maastricht Criteria further.

The EU's extended set of criteria already aims to limit the building up of private debt in less developed countries. As debt (lending) generates money, the catching-up potential of these countries (the chance of internal capital formation) has further decreased. In a depressing environment that considers budget equilibrium as a good thing what we must have, extreme political ideas are spreading again, just like in Germany after the First World War. (In the 1920s, the Germans were overwhelmed by a huge obligation of reparation by the narrow-minded politicians of the age.)

Maastricht targets are unnecessarily tight.

The origin of the target numbers of Maastricht Criteria

Part I: The fiscal creature turned against its creators

Part II: The uncontrolled philosophy of the inflation policy

Part III: Crisis because of the target numbers?

Part IV: Crisis management or panic excitation?

Part V: Clumsy clamping of the Maastricht criteria