A németek tényleg szegényebbek lennének, mint a spanyolok, olaszok meg a görögök?

Are Germans really poorer than Spaniards, Italians and Greeks?

Paul De Grauwe, Yuemei Ji 16 April 2013

https://voxeu.org/article/are-germans-really-poorer-spaniards-italians-and-greeks

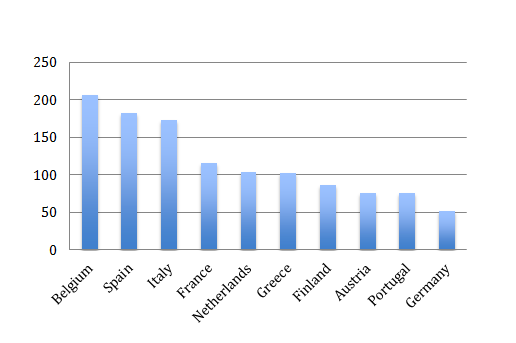

1. ábra A medián nettó háztartási vagyonok (1000 euró) Forrás: EKB 2013

Forrás: EKB 2013

Az Európai Központi Bank (EKB) egy nemrégiben (2013-ban, megj: a fordító)) közzétett háztartási vagyon-felmérését egyes sajtótermékek úgy értelmezték, hogy szegény németeknek kell fizetniük Dél-Európa nehézségeiért. Írásunkban megpróbálunk eligazítást nyújtani a közzétett számok valódi jelentését illetően. Noha a “medián” német háztartás tényleg szegényebb a dél-európai társaikhoz képest, de maga Németország gazdagabb déli társainál. Itt fontos megjegyezni, hogy ez a vagyon nagyon egyenlőtlenül oszlik meg a németek között, de a súlyos egyenlőtlenség problemtikája nem kapott kellő hangsúlyt a sajtóban. Ez a fajta diskurzus azt a nem egészen pontos érzetet keltheti a kevésbé tehetős németek körében, hogy a transzferek igazságtalanok.