Laszló Náray, István Zsadányi

Published: 03.12. 2015. (Napi Gazdaság printed, online)

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble said: "Sustainable economic growth cannot be built on debt piles". Every neat, puritan housewife in the microeconomic level would agree with this, but unfortunately, it is injurious demagogy. Although we can imagine a growing economy on barter trade (without the use of money), the expanding world economy does require increasing debt, if the players love to save money.

It is an accounting fact that the creation of a money unit in the system means even the creation of an equivalent unit of debt-entry. The things which seem to be separated, are interconnected in reality.

If saving money is good merit (instead of consuming), then the mountains of debts should be considered as a natural part of the development - concerning the macroeconomic level.

“One is led to a new notion of unbroken wholeness which denies the classical idea of analyzability of the world into separately and existing parts … We have reversed the usual classical notion that the independent ‘elementary parts’ of the world are the fundamental reality and that the various systems are merely particular contingent forms and arrangements of these parts. Rather, we say that inseparable quantum interconnectedness of the whole universe is the fundamental reality and that relatively independent behaving parts are merely particular and contingent forms within this whole.” (David Bohm, On the Intuitive Understanding of Nonlocality as Implied by Quantum Theory)

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble said: "Sustainable economic growth cannot be built on debt piles". Every neat, puritan housewife in the microeconomic level would agree with this, but unfortunately, it is injurious demagogy. Although we can imagine a growing economy on barter trade (without the use of money), the expanding world economy does require increasing debt, if the players love to save money.

It is an accounting fact that the creation of a money unit in the system means even the creation of an equivalent unit of debt-entry. The things which seem to be separated, are interconnected in reality.

If saving money is good merit (instead of consuming), then the mountains of debts should be considered as a natural part of the development - concerning the macroeconomic level.

The EU's drama is driven by Schäuble's economic demagogy: as a result of the US mortgage crisis, everyone argues in favor of increasing reserves and reducing debts of their own homelands. The withdrawal of funds from underdeveloped regions, which were growing with the use of these resources, has led to a lack of money there, speculative horror, and shrinking GDP.

According to fashionable misconceptions, our difficulties were caused by the money-wasting operation of the welfare states. This sin justifies the brutal cutbacks in the budgets of social policies. In the previous sections of our series, we have shown that there were no serious fiscal problems with the governments prior to 2008, the private debt stocks were made up precisely by those market mechanisms which were fully liberated by the states.

For teaching purposes, the budget balance has been set as "self-worth". Had it not been banned for moral reasons, the central bank could finance the deficit thereby avoiding a state bankruptcy.

Prior to 2008, financial savings had been steadily increasing, so the debt stock had also increased at the same pace in the financially closed economy of the EU. The ratio of total debt to GDP has also risen, but this has not been taken into account in the culture of balanced budget believers, as budget ratios have improved due to GDP growth. The share of public debt has decreased in terms of the volume of total debt.

A section of society has benefitted from an increase in wealth. As a result of this increase in wealth (liquidity abundance), was the debt growth of the rest of the private sector, the debt growth being above the GDP growth rate.

Free market processes have placed a large part of the private sector in a 'sensitive' (vulnerable) situation. We need expanding demand and income to keep our previous level of consumption even after paying our monthly repayment installments. Blaming the “irresponsible” creditors and borrowers for the financial crisis is intellectual laziness: in global competition, creditors and debtors are rivals and not co-ordinated office colleagues - they do not have common business strategies and planning platforms. A cashless business (or country) can only increase its capital if, in the good times (when the good times are rated “good” by the credit rating agencies) it takes risks, takes out credit in the hope that its growth will be greater than its repayment obligations.

The fact that lending was responsible or irresponsible is mostly determined by the performance of the debtor (debt recovery). It is difficult to accept Schäuble's accusations when the break of the overall growth rate was mostly because of the measures and the frightening statements of the leaders of the creditor countries. These communications and measures led to a sudden withdrawal of funds exactly at those times when the market expansion would be most needed for the debtors.

In this case, debtors not only lose their assets purchased from the loan, but their previously acquired assets could also be liquidated. The foreclosure is as if the lender had bought something from the debtor: the creditor's deposit money and the debtor's debt are both reduced, money is deleted from the system (at the same time the creditor is enriched with assets).

Debt mountains can vanish when the supersymmetry of exchange and barter is in place, the former net creditors start to consume the net debtors' products, so the accounting entries of financial savings and debts can be deleted. The Germans should be sent on holiday now for getting closer to this financial supersymmetry at the EU level.

It would be more realistic to tolerate higher debt ratios and concentrate on the increasing ability of debtors to pay - using tools of stimulation which are adapted to the local problems. This would be easy to implement, but the Maastricht criteria make this impossible because it was built on the omnipotence of free-market mechanisms, where the government's ability to spend money is a danger.

While the obstacles to the free movement of goods and services, labor and capital were abolished, central banks were also banned from direct financing of their own government, and the Member States were banned from helping each other. The literature in the theory of optimal currency areas considers risk management based on international fiscal transfers to be necessary. This was ignored by the creators of the euro, preferring to implement the same degree of price stability as the main goal. Price stability was believed to be achieved through a rigorous fiscal policy. That is why central banks (and co-states) were banned from financing government deficits.

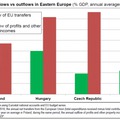

Cost-effective entrepreneurial capital has made good use of the trade margin and extra profit opportunities in the 40-80 % wage and price levels: from developed countries with more expensive hourly wage rate, huge production capacities have been transferred to regions with cheaper labor.

The extra profit resulting from increased cost efficiency has produced extra savings because the winners of the process did not increase "sufficiently" their consumption.

With an increasing amount of financial savings, there was a need for a higher return with the help of the financial intermediary system. While the state has reduced its role in redistributing income, banks have played a huge role in the re-allocation of this increasing amount of money.

Abundance in liquidity has enabled banks to safely maintain long-term receivables (such as mortgages) with renewable, short-term funds, and it pushed the interest down. Liquidity managers boldly financed public and private debts in underdeveloped regions due to relative interest margins – before 2008.

The natural consequence of the EU merger process is that, as a result of production organization and market expansion, the parent company and the foreign subsidiaries have a creditor-debtor relationship. As a result, the net foreign debt of the emerging region may have grown so that it was virtually in no financial danger because a parent could be expected to help their child when in difficulties. This is a completely different relationship to the impersonal money market where suddenly a panic wave breaks out at the slightest scratch and the resources may run out.

However, the data of speculative movements seem to have been distorted by investors scared by the credit rating agencies: in 2008, those countries which were ranked as most vulnerable, so the yield expectations increased there, where the net foreign debt was higher, regardless of the composition of the given debt. As a self-fulfilling process, this has led to the withdrawal of funds in the money markets of the countries concerned, so the most significant correlation of interest rates had in 2009 was the balance of payments data for 2008.

Although a widespread wave of debt panic was launched after the inter-bank panic in October 2008, the public debt ratio was not yet at the center of attention in 2009-10: the higher the government debt ratio, the lower was the real interest rate. Although the more developed countries were more indebted at the public debt level in 2008 than the underdeveloped, their real interest rates were lower.

The disruption of resource supply and rising interest rates have led to the postponement of development, so production was constrained, layoffs increased, especially in less developed countries. The economy slowed down, but clocks did not. It reduced the time-proportional performance of GDP. Budget revenues have fallen in line with countries' slowing economies. Due to their nature, governments expenditures could not adapt immediately, so the deficit ratios increased on average to 7% in 2009-10.

The slowdown in income generation further complicated the long-term mortgage crediting and lending, as the usual liquidity, especially in the Mediterranean region, disappeared from financial institutions that rolled long term credits with short-term receivables.

The first reaction of the EU and governments was a move in the right direction, trying to stabilize the situation and the financial market mood by recapitalizing banks. Cash flow improved, EU aggregate GDP started to grow from the low of Q3 in 2009, and in 2011 it reached its 2007 level by the end of the third quarter. The crisis seemed to be over.

The recovery was halted by the tragicomic episode of the Greek public debt in 2010/11. The Greek government's payment difficulties called attention to the evolution of government debt rates of other EU countries unfortunately at a time when the slowdown and bank consolidations raised these indicators by an average of18 % ( nobody paid enough attention to the fact that the fiscal, inflation and interest ratios were in good shape prior to 2008, so it is all right. Things happen.)

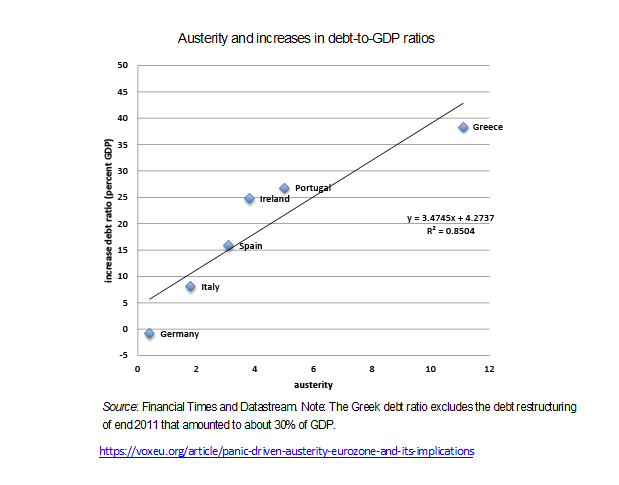

The fear from possible insolvency of the given state became the biggest source of fear by 2011, which again triggered self-fulfilling market processes: the yield expectations of the countries concerned increased (i.e. their markets became riskier), their governments started to tighten the budget in order to reassure the market.

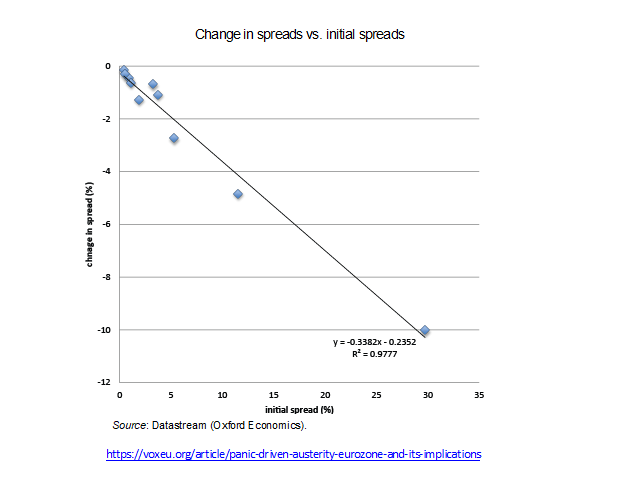

The natural way out from our debt is the increasing demand for our products, so the cutbacks of government spending made the situation more difficult for us, for the population and companies. The greater the cutbacks were, the greater were the declines in GDP, thus the deterioration of the government debt ratio (see Chart).

While EU leaders want to meet the expectations of the market, they haven't noticed something quite important!

In 2012, it became clear that market traders were happier with the central bank's ability to pay instead of the government than they were afraid of an increase in the government debt ratio!

The yields have dropped dramatically to Mario Draghi's announcement, which implies a message that the ECB may buy government bonds. The yield expectations (as shown in the figure) started falling as a result of the announcement.

It seems that market traders would welcome governments’ attempts to stimulate general demand. This would require centrally declared higher-tolerance debt and deficit ratios, and ease the requirements for central bank independence (diminishing fear of bankruptcy).

In our concluding article, we summarize the role of the Maastricht logic based on the omnipotence of the market and the fear of public debt in the recovery of private debt and deepening of the crisis.

You may also interested in:

The origin of the target numbers of Maastricht Criteria

Part I: The fiscal creature turned against its creators

Part II: The uncontrolled philosophy of the inflation policy

Part III: Crisis because of the target numbers?

Part IV: Crisis management or panic excitation?

Part V: Clumsy clamping of the Maastricht criteria