László Náray, István Zsadányi

Published: 03.04. 2015. (Napi Gazdaság printed, online)

“What is the source of all this trouble? … Yet it looks as if the thing we use to solve our problems (thought) which is the source of our problems.” (David Bohm)

We are now showing that between 1999 and 2007, the market mechanisms of cost-efficiency have resulted in faster inflation in less developed countries than the EU average, this being a natural side effect of development.

While the same spontaneous market process improved the fiscal indicators, it created those private debt mounds in the EU, which triggered self-fulfilling pessimism of neoclassical thinking since 2008.

In our previous articles, we stressed that if the central banks could finance the deficit, then it would be impossible for the state to go bankrupt. However, since the 1980s, in the name of the neoclassical revolution, the central banks have been banned from financing deficit, as soft-budget governments were to blame for high inflation during that era.

According to this classical philosophy, which dates back to the gold reserve origins of the monetary economy, the rapidly rising amount of modern credit money issued by governments leads to higher prices, and the easily available money delays bankruptcy of the worst companies, thus reducing the cost efficiency of the economy.

We are now showing that between 1999 and 2007, the market mechanisms of cost-efficiency have resulted in faster inflation in less developed countries than the EU average, this being a natural side effect of development.

While the same spontaneous market process improved the fiscal indicators, it created those private debt mounds in the EU, which triggered self-fulfilling pessimism of neoclassical thinking since 2008.

Let's examine the performance of the European Union as if it were a single country with differently developed regions! Based on the classical approach, we see a picture of a country that enjoys great health.

The course of development

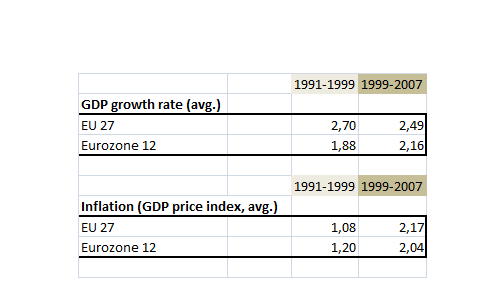

The average economic growth and inflation in the EU and the euro area were steady (2.5 and 2.2 percent) between 1999 and 2007, with only slight fluctuations. The annual rates fluctuated, on average, by1% ( excluding 2003 inflation data).

Financial features also point to balance and progress towards balance.

The balance of payments

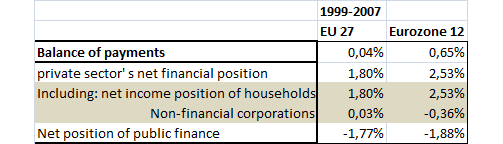

The EU-27 formed a closed economy between 1999 and 2007: the current account balance was quasi-zero, with an equal amount of debt accumulated as savings. EU-27 domestic demand is almost identical to its supply (production). In principle, therefore, it is less vulnerable to outside influences.

The problems of EU are data-interpretation misconceptions: it is a natural fact that member states (different economic regions) have different balances of payments. The passive balance of one country is the national reserve of another.

The fiscal perspective

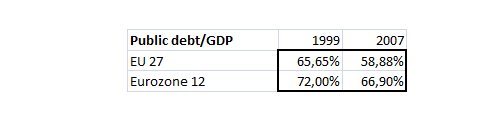

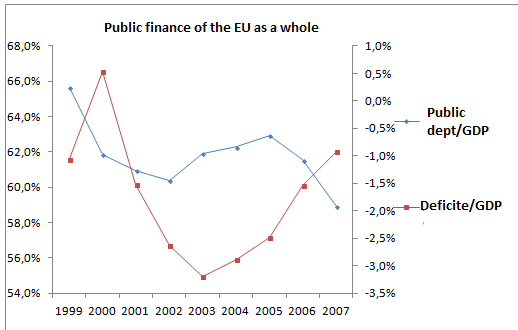

Fashionable, but unfounded moralization, that the EU crisis was caused by an unsustainable welfare system, loose budget, so the deficit must be reduced. This misconception is probably caused by the budget problems of Greece, but the Greeks, who are contributing only about 2-2.5% of EU GDP do not reflect the trend of the EU as a whole! In fact, the unified deficit of the EU countries has improved significantly, and the public debt ratio has also declined, reaching close to the 60 % level (see chart).

On the surface, everything seemed okay, the budgets were roughly balanced. The private debt stocks were built up without attracting attention. After the 2008 mortgage crisis broke out in the USA, the data relating to private debt came to light even in the EU and suddenly being faced with the financial realities caused panic amongst opinion leaders. The self-fulfilling speculative waves started to spread. This structural effect can be understood by examining the situation of countries in terms of their level of economic development.

The neoliberal reforms that created the Union, on one hand, strongly constrained the fiscal and monetary independence of Member States through the Maastricht criteria (Mc).

On the other hand, national economic protectionism has been outlawed: customs duties have been abolished and the free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital has been allowed.

The huge differences in wage and price levels between developed and underdeveloped countries were a sweet temptation for the entrepreneurial capitalist to take advantage of their potential for trading margins and extra profits.

Some data to illustrate the differences: In 1999, compared to German wage levels, Romanian and Bulgarian wages were at 5%, Polish, Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian wages were at 15%, Greek, Portuguese, Cypriot and Maltese wages were at 40%, and the Spanish wage level was only at 66%. Cost-efficiency logic has been validated: business decision-makers have relocated production capacity to underdeveloped regions to a significant extent from developed countries. This process has stimulated the economy in underdeveloped countries. It has affected both economic growth, wage and price levels.

The wage level as a competitive item

Due to the relocation of production, the growth of underdeveloped countries has accelerated. In developed countries, wage growth has slowed, but wages could grow faster where production was outsourced. Here, wage increases have pushed up prices, while lower-priced products have curbed price increases in developed countries.

Although the real growth rate, inflation and wage levels of the underdeveloped countries were significantly higher than those of the developed countries, the price and wage levels are still significantly below the level of developed countries.

The different real wage growth rates deceived many renowned economists, even the Nobel Prize winner Krugman wrote in 2012 that "Manufacturing in Europe’s south became uncompetitive…” Well, in 2007, the Spanish workforce was still 22 percent cheaper than the German. However, the eastern European workforce, who worked for German capitalists were still much cheaper.

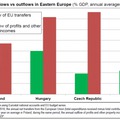

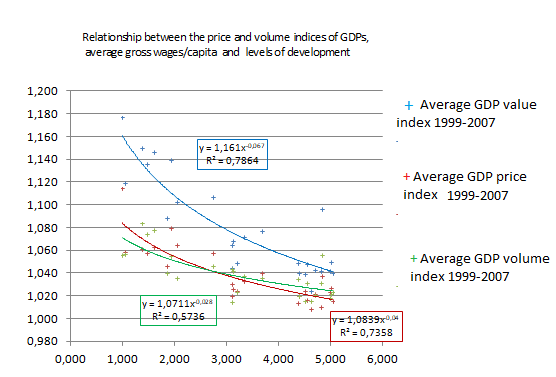

The Slovak wage level reached only 27% of the German wage level by 2007, and it is well known that the Hungarian employees work for a fifth of German wages in the Hungarian Mercedes factory. In the figure illustrating the indices, the level of the most underdeveloped country on the horizontal scale is indicated by 1. It can be seen that in 1999 there was a five-fold difference in the level of development within the EU countries. The lines show that the more underdeveloped a country was in 1999, the faster the average increase in inflation, economic performance and wage levels per employee between 1999 and 2007. Relationships are very strong in the statistical sense.

Price level and inflation target

In 1999, the Hungarian, Polish and Czech price levels were lower by 66-68% than the German price level, the Romanian by 80 %, the Spanish and Greek at around 30%. The more underdeveloped a country, the lower the initial price level, so it seems understandable that the underdeveloped countries' inflation (here: closing the price gap) was much faster than that of the developed countries.

The Maastricht criteria consider price stability as the main objective in everything. The price increase in the accession countries in the years preceding the introduction of the euro may not exceed the average of the three lowest inflation countries by 1.5 percentage points.

If a 66% difference in the price level can only be processed in 1.5% steps, the Hungarian, Czech, and Polish are going to take more than forty years to catch up.

If, however, we consider the introduction of the euro within five to six years, it would tolerate up to 10% extra inflation. According to the neoliberal association, "inflation is always a monetary phenomenon", most probably caused by a loose fiscal policy. The central bank should respond to inflation either by raising interest rates or maintain high-interest rates.

However, the higher inflation rate can be explained as the consequence of the new relations between the regions with different price levels, not just by the overspending of governments. Despite higher inflation, the Spanish and Greek price levels did not reach 90% of the EU average by 2008, with Polish, Czech, Slovak and Hungarian price levels reaching about two-thirds of the EU average.

Interest rates, savings, indebtedness

The winners of the EU market unification did not increase their consumption in proportion to their surging incomes, and the ‘increasing savings crowd’ was looking for a return on capital through the financial intermediary system. This huge supply of sources pushed down interest rates. The relocation of production contributed to the weight of savings the best in the developed countries, resulting in very low deposit rates. In liberalized money and capital markets, financial institutions of developed countries were able to deposit this inexpensive money in the underdeveloped countries at a higher interest rate and/or long maturity.

As a result, in the underdeveloped countries of the eurozone and in those which relate/link their currencies to the euro, lending costs - despite higher inflation - have fallen to a low level close to that of developed states.

Outside the eurozone, the rigid interest rate policy of the central banks seeking to curb inflation has only strengthened the exchange rate of domestic money, while their inflation was significantly higher than that of the euro area.

In these countries, low euro interest rates strong domestic money and higher inflation combined, have provided an excellent opportunity for governments and the private sector to make debt on foreign exchange. The attractive "loan/value" indicators of rising price levels have greatly strengthened banks' lending activity and competition, which has become an interest-reducing factor in these countries.

Market interest rates in the euro area declined up until 2006. In 2007, in response to the emerging financial problems in the US, market interest rates increased, although remaining below 2002 levels. In non-eurozone countries, interest rates declined in general by 2007. Thus, the convergence of prices and interest rates has become contradictory.

In the less developed euro area (Mediterranean region) and in the Baltic states this mechanism has created a negative real interest rate, because the price level has increased faster than the interest rates, thus stimulating borrowing. It is quite understandable that real estate projects and real estate financing rose before 2008 in a favorable Mediterranean climate. Real interest rates also fell in other underdeveloped countries with independent exchange rate regulation, and the real rate of foreign currency loans became very low.

The banks' ability to create more money increased significantly in the era of low-level real interest rates: a significant part of the money disbursed in the course of increasing credit activity landed on the bank accounts of the sellers (producers), which was a new source to further credit activity. The rate of the increase in the level of debt (loan) and savings (deposits) of the private sector (corporations and households) was higher than the rate of increase in wage income. In underdeveloped countries, debt, and in the more advanced regions the savings increased faster, in line with the evolutions of real interest rates.

The EU balance of payments was in leveled in 2007, and its monetary economy could be considered essentially closed. If the saving is great merit and the "cash is king", then the formation of private-sector debt stocks (which is the formation of money-savings at the same time) should be seen as a natural phenomenon which goes along with the economic development.

In our next article, we will show that the European crisis began to emerge when, as a result of the US mortgage crisis, opinion leaders began to focus on debt data of different locality and types, and then they become frightened from them without taking into account broader contexts, thus self-fulfilling processes have been launched.

You may also interested in:

The origin of the target numbers of Maastricht Criteria

Part I: The fiscal creature turned against its creators

Part II: The uncontrolled philosophy of the inflation policy

Part III: Crisis because of the target numbers?

Part IV: Crisis management or panic excitation?

Part V: Clumsy clamping of the Maastricht criteria