Laszlo Naray, Istvan Zsadanyi:

Published: 02.23. 2015. (Napi Gazdaság printed, online)

...there is no such thing as philosophy-free science; there is only science whose philosophical baggage is taken on board without examination." (Daniel C. Dennett)

Let us now check the philosophical baggage we took on board ( without prior examination in 1992) when we all agreed to use the same inflation target numbers, as decreed by the Maastricht Criteria.

In our first article, we called Maastricht criteria (MC) " The tyranny of numbers". International institutions built on these criteria (i.e. coerced fiscal convergence, excessive deficit procedure and the adapted market and credit rating rituals) are forcing states to raise taxes and reduce expenditure in order to reduce their GDP-proportionate deficit exactly within those given time-lines , when the spontaneous market mechanisms alone are unable to generate sufficient incomes - although the IMF itself showed in a comprehensive study in 2012 that 1 % austerity on average resulted in a 1,3 % decrease in the GDP.

What could be the reason why the budget balance is considered to be a vital issue in spite of the proven fact that the austerity logic has created a great deal of insufficient damage? Why are the central banks not allowed to give money to those governments in need? And why is it bad if public debt exceeds 60 % of GDP, while private debt is over 200 % of GDP in more developed, well-functioning countries? Didn't we mix the tool with the goal? What is the goal at all?

In 1983, Thatcher declared her belief that the state has no source of money other than the people earn themselves.

Since then, several generations of economists have grown up in the context of the institutional system (meme complex) built on this statement. They have not been able to compare the circumstances of the birth of this belief - for example - with the problems of our time. These generations see Thatcher's statement as ‘obviously’ true. The neoclassical (otherwise neoliberal) philosophy is the denial (antithesis) of a previously dominant economic logic. The "neo" indicator is there because it follows the original classic thesis of Adam Smith, who worked approx. 200 years ago. That is why we present the economic logic which was used between the classical liberal and the neoliberal ones, and which was denied by Thatcher and her neoclassical followers.

According to the classical view, we should free the profit-seeking individual interests. It can only result in a stronger, more functional economy than the one, in which the government is arbitrarily allowed to try to influence - encourage or restrain - the different players.

Before the neoliberal economic times, the bankruptcy of the state was impossible (in its own currency). The central bank was free to assist the government, so the state did not have to raise taxes in order to pay its market creditors in time.

In the absence of tough budget constraints, the state was able to stimulate the economy with the development of the infrastructure of the transport and social care systems, even when spontaneous mechanisms, for example, due to a market panic, were unable to do so because neither investors nor households dared to spend, and consumption began to fall dramatically.

However, the economist, Milton Friedman, who had a great impact on Thatcher, considered that it was not only the oil price explosion, which made the GDP stagnate in those times, but there was too much government spending from paper money, for example, because of the trade unions which kept on demanding higher and higher wages and welfare benefits.

The price of oil exploded in 1973 by the Jom Kippur war and the oil embargo against Western countries. Workers demanded wage increases in the years of the oil price explosion, and if they could not achieve it, they simply chose unemployment and the benefits paid, at least according to Friedman. On the other hand, the increase in costs, due to increased wages led to inflation, so the purchasing power of higher wages did not improve, while wage increases resulted in higher inflation expectations. Indeed, left-wing governments were frequently prone to subsidize troubled companies thereby avoiding conflict with trade unions.

For the inflation, the neoliberal Friedman laid the blame on the soft budget.

The constraints promoted by Thatcher (i.e. decreasing the quantity of money) were, on the one hand, supposed to break down the wage-price spiral, and on the other hand, intended to stimulate management of the private sphere to invent energy- and cost-effective solutions. The aim was, therefore, to create a low inflation environment by a limited quantity of money, encouraging cost efficiency. One of the tools of this was to ban central banks from financing the deficit.

The dollar's quasi-gold cover was abolished in 1971. Until ’71, the US had to convert its deficit into gold if its partner, who was in surplus, applied for it. The French De Gaulle applied for it. The answer was that the US had rather abandoned this whole system in 1971, the exchange rates have been floating free since then. It is understandable, therefore, that the conservative advocates of the gold-system were frightened of price increases and called for a rock-solid regulation of money issuance.

However, inflation could be explained by the oil price rise.

The oil price explosion started in 1973. The extent of it was incredible: it has multiplied by thirty times in a few years. Imagine that the price of fuel per liter would increase from 1 euro to 32 euros! This would be "cost-driven" inflation. No wonder the attempt which tried to interpret inflation as a "wage-price spiral", did not earn the support of the majority at the first attempt.

However, Milton Friedman was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976, and Thatcher, who spread Friedman’s views, came to power in 1979, so the situation changed. Then the West eventually survived the oil crisis, while the Soviet Union broke up in 1991: the neo-liberalism that set the budget balance as sanctity seemed to be the winning logic.

Then came the year of 1992.

The economists who created the Maastricht Criteria considered as the best method for catching up of the less developed countries if the government's room for maneuver was limited by the 3 % deficit ratio and the 60 % public debt ratio. The tolerable inflation and interest rates are set to reference data for the lowest inflation and interest rate countries, with a maximum of 1.5 and 2 % overflow.

The condition that fiscal conditions (debt and deficit ratios) in the member states should be the same, has never appeared anywhere before in the literature on optimal currency areas. The justification for the debt ratio criterion was also questioned by the example of the only former and functioning currency union in Europe that existed between Belgium and Luxembourg: in 1997, the former had a GDP ratio of 122%, the later around 7 % of GDP.

The philosophy of budget equilibrium is like the renewed logic of commodity money.

It was the ultimate triumph of the neoclassical school above the former ruling economic philosophy which handled the fiscal policy as a discretional tool so the budget could have been adjusted with relative freedom to the needs of the situation. (Let’s call it as the “discretional governance school”)

MacDougall Commission

The neoclassical minds think that the base for every further success is the limited budget and price stability. Before them, the advocates of discretional governance have proposed a completely different convergence path. Their proposal was developed by the MacDougall Commission for the EU which had only nine members in 1977.

The committee led by Donald MacDougall examined the co-operation between regions of five federations (USA, West Germany, Switzerland, Australia, and Canada) and three countries (France, Great Britain, Italy) and the history of catching up with underdeveloped regions.

Professionals have come to the conclusion that income-convergence should be focused on rather than the convergence of national or regional budgets.

The objective of catching up is to reduce economic inequality within the EU. They suggested that the average income per capita - the levels of development - should be equalized as soon as possible.

The MacDougall Committee did not propose target numbers for the budget deficit and public debt. Members were aware that, at the time of catching up, the abolition of customs duties, the free movement of capital and goods could cause local shocks in underdeveloped regions, and that potential local depression would require priority subsidies and other income transfers.

The victory of neoliberal antithesis

With the victory of neoliberal antithesis, the proposals of this committee have disappeared from the negotiating tables, and the Maastricht criteria of the Delors Committee have become the pillars of the euro. MacDougall himself predicted that this euro system would not be good for the member states. He seems to be right.

Monetary criteria make sense at first glance. If we are citizens of an advanced, low-inflation country, it seems legitimate to be worried about the higher inflation rate of our neighboring region. We see it as a credibility loss in money, a dangerous social impact of the soft budget.

Although price stability has been the prime target of central banks in the European Union, inflation, in spite of our natural intuition, is not necessarily bad. It rather should have been interpreted as a side-effect of growth or catch-up in most Member States.

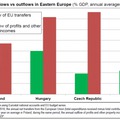

In 1999, the Hungarian, Polish and Czech price levels were lower than in Germany by 66-68 %, in the case of Romania this figure was 80 %, in Spain and Greece it reached 30 %.

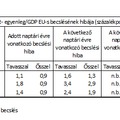

If we accept that there is a close correlation between wage and price level convergence (this will be confirmed in the next article with factual data), we can see that the fight against rising prices through the interest rate policy and the strengthening of the exchange rate it distorts the economic structure at the expense of domestic producers (due to the deterioration of competitiveness and rising investment and consumption credit interest rates).

If the 66 % difference can only be worked in 1.5 % items, then theoretically, we are going to have more than 40 years to catch up (66% / 1.5% = 44 years). However, when, for example, in Hungary the experts talked about the introduction of the euro in five or six years - apparently only focusing on the fiscal condition in 2000, it could also have meant that up to 10 percent of additional inflation could be tolerated (66% / 6 years = 11%). However, this would collapse the philosophical structure of EU convergence on inflation of 2 %.

The creators of the MC did not take into account the huge differences between the price levels of the countries facing EU coexistence. Thus, governments forced to follow the goal of price stability had to deal with price level convergence as "guilty" inflation. In our next article, we show that convergence of price levels was a natural feature of free-market mechanisms seeking cost efficiency.

You may also interested in:

The origin of the target numbers of Maastricht Criteria

Part I: The fiscal creature turned against its creators

Part II: The uncontrolled philosophy of the inflation policy

Part III: Crisis because of the target numbers?

Part IV: Crisis management or panic excitation?

Part V: Clumsy clamping of the Maastricht criteria